In Depth with the Former Superintendent

(from the archives)

April 5, 2020

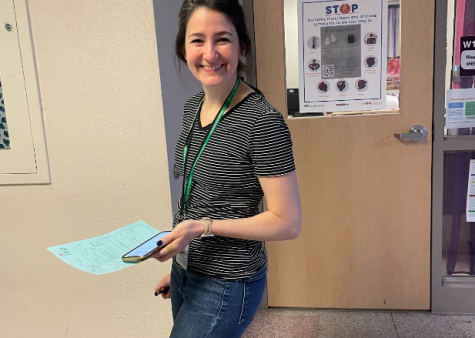

Recently, education around the United States has faced seemingly endless issues, whether they be school violence, lack of funding, or ineffective policies. The student community is feeling ignored by adults, the administration, and the federal government. All around the country, we have had an amazing number of our student community take a stand against these injustices. But there are adults in our community who want the same things we do. Jane Sigford, a former superintendent of multiple suburban schools in Minnesota, is a prime example. I asked her a few questions about her experience as an educator and how she feels about particular issues in our educational system.

Q: Could you summarize your career as an educator?

A: I started out as an English teacher, and then got my license to teach learning disabled and emotionally disturbed high school kids. I also had a masters in English with a focus on black literature. Then I got my doctorate in Educational Leadership and Policy. So I started as an English teacher then became the first EBD teacher ever at Eden Prairie High School, then their first dean of students, then left there to become an assistant principal, then I was the high school principal, then I became the executive director of curriculum and instruction, then retired from there. Throughout that I have taught at St. Thomas and Hamline University.

Q: What would you say was the most gratifying part of your job?

A: Working with kids. And when somebody learned something, and they’ve worked hard to learn it, and they do, it’s just really fun. And when you get kids excited about learning and they ask questions. And adults too. When people learn something it’s just a rush. I like working with kids who think they don’t like school for one thing, we can have a lot of fun and it’s about a relationship with kids. Most kids really do want to learn, it’s just a matter of lots of things going on in their life. Many of my student just didn’t fit the sit down shut up way of learning. There are three of my students that I know of who have successfully committed suicide, and two of those were extremely bright men, but they just didn’t fit school.

Q: What was the most difficult or stressful part of your job?

A: Being a high school principal was probably the most stressful for me, because that style of leadership isn’t mine. That’s really a top-down style of things to do. But the most difficult part of it is dealing with adults, particularly crazy parents and teachers who don’t do what they’re supposed to do. I was surprised on how much time I spent on personnel issues. It wasn’t about kids and it wasn’t about education. It was about adults bad behavior – teachers’ bad behavior. Also, many of my students just didn’t fit the sit down shut up way of learning. There are three of my students that I know of who have successfully committed suicide, and two of those were extremely bright men, but they just didn’t fit school.

Q: How did being a woman in this community affect how you were seen by others?

A: Being a school administrator is designed on a very male style of leadership – it’s very top-down. Very authoritarian. I found out that people don’t take you seriously as a woman unless you cry or yell and scream. And I don’t like to do either one of them. But if a man and a woman say the same thing, men are considered leaders and women are either considered bitches, or a whiner, or not a leader. We really have not gained in numbers women who are principals in the state of Minnesota.

Q: Did your gender influence how hard you had to work?

A: I had to work differently. Anybody who takes those jobs seriously works hard, whether they are a man or a woman. I worked differently. I had to learn to do different things. When I was the curriculum director I had a set of resource teachers who I worked very closely with. But I would have ideas or they would have ideas and we would have to do a lot of teamwork. And that was really fun to learn from each other because it wasn’t about gender. It was about providing support for each other.

Q: What was an advantage of being a woman?

A: (long pause) I don’t know. I was often one of the first women to do something, and maybe that was an edge. I was in the right place at the right time.

Q: In the schools you worked in, where there any incidences of violence or fighting?

A: Yes definitely. Fights. I ruined a suit one time breaking up a fight and got blood all over it. I had a loaded nine millimeter handgun running through the school in the hands of a kid. There were no school shooting threats. It was not in an urban high school, by the way, I want to make that clear. That was a long time ago too, before all the school shootings. The first school shooting in the United States was in the early 1700s. School shootings are the site of the deadliest mass shootings in the United States because they open fire in a cluster of people.

Q: How do you think working in our modern society of school shootings as a normality would differ from your experience as an educator?

A: Right now there’s a research study by two men who are specialists in school violence and they say if you really want to change violence in schools, what you do is have a community health approach where schools and police departments and community health and social work departments work together as a mental health focus, not just putting up more glass and metal detectors. Cause it’s gotta be about that. It’s gotta be about dealing with issues when people feel disenfranchised or have mental health problems. And we haven’t come to that. Putting up more glass and metal detectors isn’t going to stop school shootings. I also know that people don’t feel as safe as they used to. One of my schools used to be able to keep the doors open and students could study outside. And then Columbine happened. And they were no longer able to do that. It’s sad. But I don’t know what to do about making kids feel safe. I am extremely proud of the youth of the United States who have spoken up to challenge our legislature. It reminds me of the Civil Rights escapades of the 60s. I’m really disappointed the Minnesota legislature didn’t pass anything to change the guns laws even though the poll in the Star Tribune shows how, percentage wise, people in this state want some change. And it’s divided by gender, metro vs. outstate, Democratic vs. republican, and age.

Q: Having worked in the field of education for quite a while, do you have any ideas about how schools could prevent shooters from attacking them?

A: The irony is in some of the schools I worked in, the doors are open for after school activities. So if someone wants to bring a gun to school, all they have to do is wait until 3:30 and they can just walk right in those buildings. I think there has to be a mental health component. It really has to be a community approach. Too often, everything is dumped in schools like we are supposed to be the mental health experts. We are not mental health experts. Teachers can’t, they are meant to be teachers. And we have to have more community and parent involvement. We also let parents off the hook sometimes for the way they raise their kids and that gets dumped on schools. In some districts, they feed kids breakfast and lunch even in the summertime. That’s not a school’s job. That’s a community’s job. And granted, kids need to eat, but it’s not just the schools job to feed the world. It’s not fair for everything to be dumped on schools and still be expected to teach at the same time. So I think there must be a lot more community conversations. Unfortunately, they cut back social workers in schools and the workload of some of the social workers is horrendous. It’s impossible for the social workers to deal with all of the sick adults and kids.

Q: Do you think the federal government should be doing more to prevent these attacks? And if so, how?

A: Instead if trying fund schools for academics, they should give grant for good public health agencies for local police departments. Because if you have a student that you are concerned about mental health wise, you can refer, but something may never happen. I once had a student who was in third grade and he had a written plan about how he’s gonna commit suicide. This little kid had two full time guards with him at all times. He was really mentally ill. I know he ended up in a residential treatment center. We have cut back a lot of the mental health facilities in Minnesota. A lot of mentally ill adults end up homeless or unemployed because there are no facilities for them. We really don’t know what to do to treat mental illness. They give them medication.

Q: What are your thoughts on arming teachers to prevent these school shootings?

A: It scares the hell out of me. Police officers have to have a lot of training and they have to re-license and re-train constantly to use guns. And we are going to let people who have no training ring guns to school? No. Absolutely not. What we do know about handguns is if you have one in your house they will most likely hurt someone in your family. So having a gun loose in a school, in a desk or not, most of those desks can be broken into without much problem even if they’re locked. Most people I know are absolutely not in favor of that.

Q: Was there a prominent racial divide in the student community at the schools you worked in?

A: In some. In all of them actually. Kids sit by race and gender in lunchrooms. You sit by race first, gender second. And the dances were really fun, just a blast. But there were three separate dances. The Hmong kids were in one corner. The white kids were in another corner. And the black kids were in another corner. We had a day called A Time To Think at Eden Prairie which was about racial issues. We had panel discussions and kids were able to share how they felt about being at Eden Prairie High School. That was a very powerful experience for those kids to speak up and say how they felt.

Q: Did you ever witness racial discrimination from teachers to students?

A: A lot of unconscious racial discrimination. It’s almost impossible because we have have some of those racial biases and we have these preconceived notions. And there are times when people don’t even know they are doing it. But they will look and say, “Oh, that kid is from Minneapolis therefore they aren’t going to do as well.” And that becomes a self fulfilling prophecy because they end up treating kids differently. I think they should take racial categories off of all these tests. What we should look at is where kids are and where they need to be apart from names. Take all the names off. But the more you separate by race, the less we are going to close the achievement gap.

Q: Do you have any ideas about how schools should operate?

A: For one thing, schools should be reimbursed when they make a year’s worth of growth. Schools should be based on learning. And districts could make the same amount of money whether a student graduated at 16 or 21. We could have ninth and tenth grade be a little different. The classes would be based on using the information they had gained in elementary and middle school and be much more realistic. Juniors and seniors should almost have a menu of courses to choose from such as courses in medical ethics, how you resolve world conflicts, and give people real exercises to perform. They should be out in the community and using what they have learned. The transition from highschool to college should be much more gradual. And the classes should be intermixed, not necessarily divided by grade level. We also need to stop focusing on sending everyone to a four year college. The jobs right now are from technical schools, not from college schools. And schools are also getting away from the liberal arts programs which is a huge mistake. They are not focusing on the humanity of literature and history and if we don’t learn history we have a tendency to repeat the same mistakes, which we are still doing.

Q: In your opinion, what is the biggest problem in our educational system?

A: It’s outdated. What we focus on, how schools are reimbursed, how we set up the structure of schools is outdated. We treat elementary and middle school and high school and though they are a continuum, and they’re not. Elementary needs to focus on basic things like making sure kids can read, understand and use the math algorithms, and be technologically savvy. Middle school needs to be exposed to a lot of different things like more technology, more of the arts, because some of these are life skills that people will use. They are also artistic skills right now. And then high schools need to be a lot different. The courses need to be different, we should stop teaching American history like three or four times in a kid’s life. We should teach it once really well so that kids remember it. But it should be really applicable to their life and you can do that really differently. And make them involved in the history. There should be much more connection with the world.

Jane is not the only former or current educator/adult who feels strongly about these topics. Many adults in our community feel the same way and may also have ideas for ways to improve our educational system. Star Tribune has published multiple articles regarding how the Minneapolis community feels as a whole, encouraging the student protests. If we could get active support from more people like Jane, it would strengthen and broaden the student movement happening across the country. Adults and students working together as a community to improve education could make schools all across the world much safer and more effective.